If we accept that Software is Eating the Network, then we accept that understanding and managing software within an Open Networking solution is critical to successful implementation. We now turn to Open Source Software, a component of Open Networking that is a critical multiplier of the benefits that are derived from the components we already covered, and a critical driver of the success and capabilities of Open Networking.

Open Source Software has literally exploded into the software marketplace and transformed the approach to Open Networking solutions development. For example, take Github.com, the development platform that hosts a range of software projects including open-source and was recently bought by Microsoft. Github.com was founded in 2008.

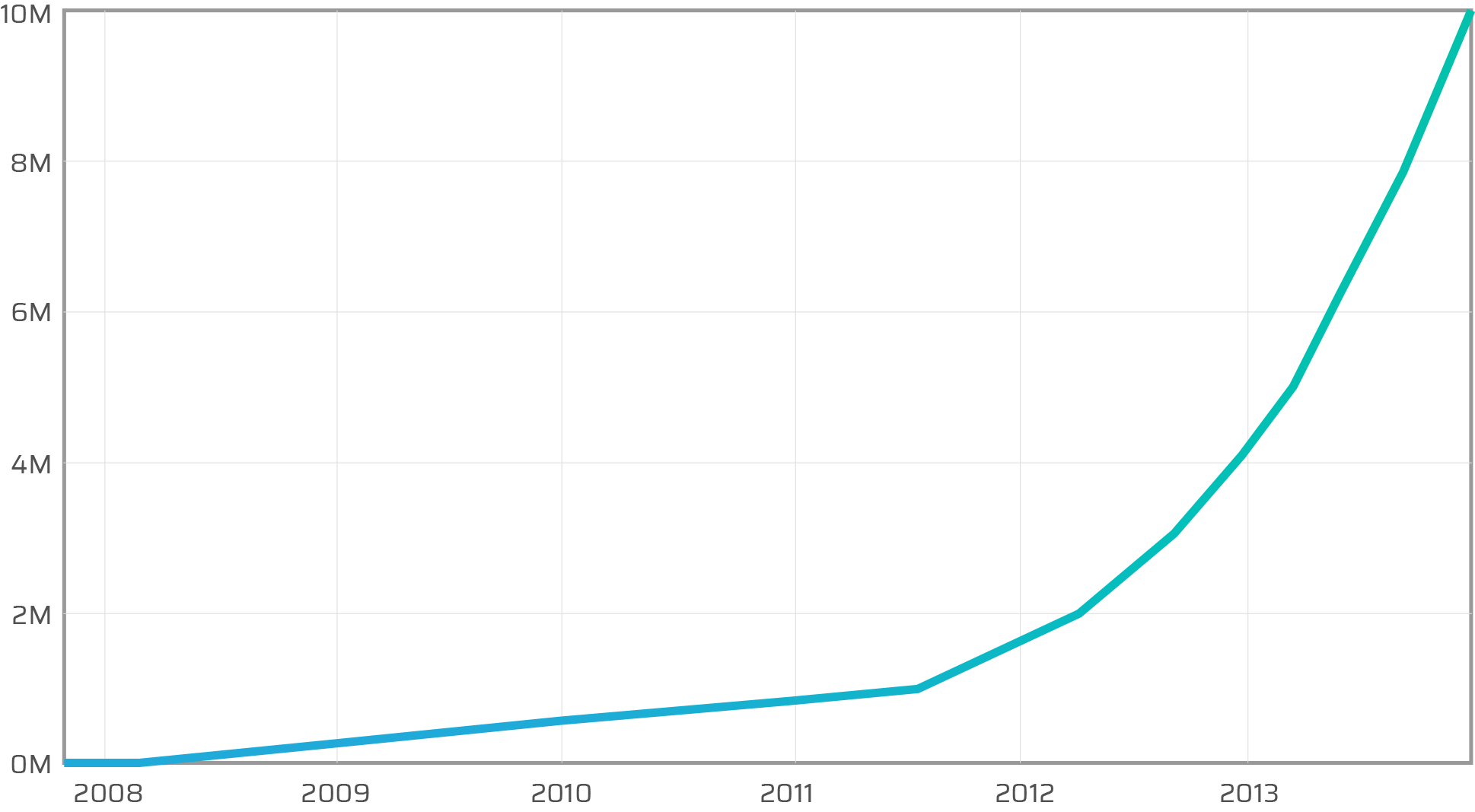

The growth in projects on Github.com is shown in the chart below:

And the trends in that chart have continued: as at end 2016, Github has 25 million repos, and 67 million at end 2017. Not all of these are Open Source by any means: in 2016, Github hosted 2.8 million open-source projects that explicitly listed Open source license agreements in the project.

As a capstone to this massive growth in Open Source, on 4th June, 2018, Microsoft announced that it was buying Github for $US7.5 billion. The CEO of Microsoft, Steve Balmer had once called Linux (and Open Source generally) a “cancer”, in 2001. Microsoft, a famously proprietary vendor, now finds most of its growth is selling Cloud services to developers, and Open Source is clearly now strategic.

What produced this massive growth in Open Source? As with networking products, frustration with vendor driven proprietary software.

Software as commercial product paralleled the development of hardware. Although free sharing of software code was common in the early days of software, commercial pressures sidelined this in the 1970’s and 1980’s. All the commercial software was proprietary: it was owned by the vendor who went to great lengths (often extreme) to prevent that intellectual property being used without compensation.

Just recently, whilst working with a well-known tertiary institution, I was reminded of how extreme software licence management was in some sectors. This institution was still dealing with an ancient licencing model based on the hardware licence “dongle” that was provided by a software vendor and had to be plugged into the computer on which the software was to be installed & run. These devices often used up a port (usually the parallel printer port) and were often buggy. But just the sheer unmanageability of these devices made them a sore point with software users and administrators.

Vendors argued that their software reduced cost by spreading development investment over many customers, and that a software product based on broad requirements inputs from many customers resulted in a more functional and valuable outcome.

But it was still only developed by one vendor, and the rate of innovation was directly related to the productivity of that one firm and a function of how much of their revenue the vendor wanted to invest in development and support. Licence costs for software became very expensive, and some software houses very profitable. It was all too easy for the vendor to drift into a “rent seeking” approach of protecting ongoing revenue without necessarily funding ongoing development, which undermined the whole economics of the business model.

Some thought that it was possible to do better:

In 1997, Eric Raymond published ‘The Cathedral and the Bazaar’, a reflective analysis of the hacker community and free software principles – (Wikipedia).

Raymond’s view was that different software development situations demanded different business / development models. In Raymond’s view, some software requirements needed the structure and formality of the Cathedral, but most could be satisfied in a bazaar-like market where products were traded easily amongst a variety of stakeholders.

The Open Source Initiative was founded in February 1998 to encourage use of the new term and evangelize open-source principles, and in 1998, Netscape released the source code to its Navigator browser as “Free Software”.

The principles of Open Source software resonate with the philosophies of the Agile movement, which was emerging in parallel:

- Users should be treated as co-developers

- Early releases

- Frequent integration

- Several versions

- High modularization

- Dynamic decision-making structure

Open source was more than just a software licencing mechanism. Open source established new business models for commercial software enterprises and drove a materially different model for the software development process itself. Numerous companies around the globe have successfully grown business that leveraged open source projects with services, “hardened” versions and support fees.

What it meant was that a code base could be developed collaboratively by many parties who could all share in the benefits, without a single vendor controlling the pace or direction of the product evolution.

Since 2011, major companies have got onboard the Open Source bandwagon, developing operationally critical software as open source or releasing in-house developments to open source communities.

With the brand recognition and financial strength of companies like Google, Facebook and AT&T endorsing the open-source approach, and operationalising business critical functionality using open source software, the Open Source approach became more mainstream.

This enables many benefits but brings with it many risks and challenges.

In the next 2 posts we will look at two Open Networking software families that were enabled by the Open Source approach and that in themselves will highlight the many benefits of this approach.

Stay tuned.